WHERE ARE AMERICA’S MOST VULNERABLE BRIDGES?

(Bloomberg) --

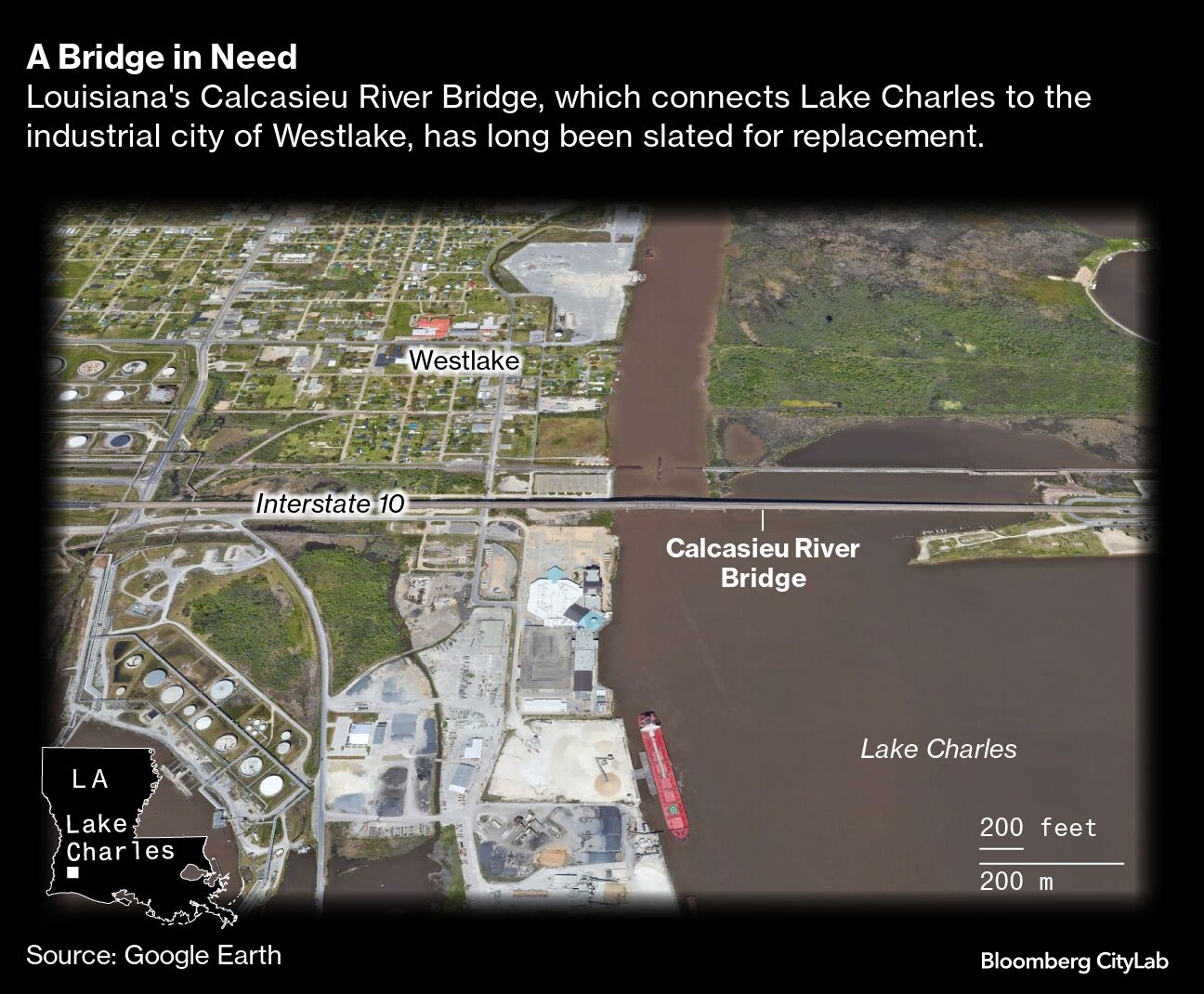

On any given day, motorists make some 87,000 trips across the Calcasieu River Bridge, which carries Interstate 10 over the north end of Lake Charles, Louisiana. That’s more than double the traffic load it was designed for when it opened in 1952. The bridge has since gone the way of much of America’s aging infrastructure: in urgent need of replacement.

In many ways, the I-10 bridge shares several characteristics with the felled Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Maryland. Both are continuous steel truss bridges spanning waterways, and they’re both “fracture critical.” That means they lack redundancy, and a failure of just one key element of the structure could eventually bring down the entire bridge, or a large portion of it.

The Calcasieu River Bridge isn’t at risk of getting hit by cargo vessels the size of Dali, the 984-feet container ship that struck the Key Bridge on March 26, causing it to collapse in a matter of seconds. But it has been struck by smaller boats in the past, including a casino barge that was blown into the bridge’s support piers during Hurricane Laura in 2020. And its deficiencies have long made it something of a poster child for America’s aging infrastructure: Plans to replace it first emerged in the 1980s, and several local, state and national leaders have pledged to follow through, including President Joe Biden, who visited in 2021 to promote his infrastructure bill, and his predecessor Donald Trump, who stopped by during his re-election campaign in 2019.

The swiftness and intensity with which Baltimore’s Key Bridge fell into the Patapsco River last month has renewed safety concerns about the vulnerabilities of other structures nationwide. Six road workers died in the incident, and the Port of Baltimore remains largely closed as crews continue removing containers and debris.

The Key Bridge — which had been deemed to be in satisfactory condition — was one of at least 17,000 fracture critical bridges in the US, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. That’s about 3% of the nation’s more than 600,000 bridges. Of those, roughly 1,700 are built over a navigable waterway with boats traveling underneath, according to Bloomberg analysis of data from the national bridge inventory.

“Fracture critical bridges are the one area where I’m most concerned,” says Wesley Cook, a structural engineer at New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. “When I’m driving over certain bridges, I know which ones are fracture critical, and I kind of cringe.”

Most modern bridges incorporate redundancy into their design to allow the structures to redistribute load in the event a single element fails, he adds. One high-profile example: After the collapse of the I-35W Mississippi River Bridge — a fracture critical steel truss structure built in 1967 that failed during rush hour in August 2007, killing 13 people — Minnesota replaced it with a concrete box girder bridge, whose segments are locked together by high-strength steel strands to provide multiple layers of protection. Hundreds of sensors were also embedded in the bridge, allowing researchers to monitor strain, load distribution and potential for corrosion.

But a large share of US bridges still in operation today were built during the highway-building boom of the 1950s and ’60s, or even earlier. And they’re showing their age.

Ranking the Risk

More than 300 bridges in Bloomberg’s analysis are considered to be in poor condition, with significant deficiencies found in at least one of three structural elements: the deck, which carries the roadway; the superstructure, or the upper portion of a bridge that bears the weight of the load passing through; and the substructure, which supports the bridge from below.

In 14 bridges, all three sections are considered to be in poor or serious condition, according to their most recent inspection reports. They include seven structures that handle an average of 10,000 or more vehicular trips daily. All were also built before 1970; some are more than a century old. As the map below shows, needy bridges can be found across the Midwest and Northeast, and there’s a cluster of them in Louisiana.

“Fracture critical” sounds dire, but the presence of fracture critical members does not doom a bridge. (Indeed, in 2022 the Federal Highway Administration updated its bridge inspection standards with the more descriptive term “nonredundant steel tension member.”) And engineering experts say that despite maintenance needs, most US bridges are generally safe to drive over. But some worry that excessive wear and tear over time can compromise a bridge in the event of a major incident. Those include strikes from ships or barges passing underneath and extreme weather, as well as chronic threats like vehicle crashes, fires or explosions.

“The biggest things we worry about are corrosion and durability on really high-traffic interstate bridges — everyday bridges that have had 50 years of road salts, and concrete or steel corrosion that’s now become very significant,” said Ben Schafer, a structural engineer at Johns Hopkins University. “The states have to judge which of its existing bridges to do repairs and upgrades, and it can’t do all of them.”

Bridges with fracture critical members are required by the federal government to be inspected biannually, and many are due for an inspection this year. That means the national database may not reflect repairs made or started in the last two years.

Maintaining the bridge’s substructure — which includes support columns, footings and abutments — is particularly important, says Amanda Bao, program director in civil engineering technology at Rochester Institute of Technology. “Damage to the substructure can cause overall collapse of the bridge.”

In the aftermath of the Key Bridge collapse, bridge pier fenders and other protective structures that can limit damage from boat strikes have received extra scrutiny. That span, which opened in 1977, did have modest fenders and “dolphins” — concrete structures intended to divert wayward ships — but Dali missed the dolphins as it drifted toward a support pier. A recent New York Times analysis found that dozens of US bridges over heavily trafficked waterways currently lack such barriers.

But retrofitting existing bridges with more robust pier protections can be very costly and many experts are skeptical that even upgraded devices could have saved the Key Bridge, given the ship’s size. What happened in Baltimore was an extremely rare event, caused by a cascade of failures in which the fully loaded Dali, which weighed more than 257 million pounds, lost power and struck a pier with a force that Bao estimated as the equivalent to 66 trucks traveling at highway speed hitting the bridge at once.

“I'm not referring to this as a bridge collapse anymore; it’s a bridge destruction,” said Schafer. “Every bridge fails if a boat of that magnitude takes out the support, so to me, the lesson is actually [about] how important supports are for a bridge.”

He adds that a catastrophe of this scale often prompts government agencies reassess risk tolerance, but it may take over a year for the NTSB to complete its investigation into the Key Bridge collapse. Federal regulators may consider changes to bridge specification, as well as to maritime policies, but that will also take time, as agencies consult with state leaders and the industry before pushing out new standards.

Such updates have come in the wake of previous disasters, such as when Tampa’s Sunshine Skyway Bridge was struck by a freighter during a storm in 1980, collapsing the bridge and leading to 35 deaths. When its replacement was completed seven years later, its piers boasted extensive fenders and protective dolphins.

In the meantime, individual state departments of transportation may review bridges that share similar vulnerabilities with the Key Bridge. “Individual DOTs will say, ‘Let’s get on the ball and see what we can do to prevent this from being in our backyard,’” said Cook at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. “So there’s always an immediate response.”

Drivers Beware

The busiest bridge in Bloomberg’s analysis is the Calcasieu River Bridge, whose structural elements were all given a score of 3 out of 9 in a December 2022 inspection report. That means they are all in serious condition, in which deterioration has “seriously affected primary structural components” and could result in “local failures,” according to the federal coding guide .

But you don’t need an inspector’s report to conclude that this is a bridge that could stand to be replaced.

It’s Louisiana’s steepest, with two narrow travel lanes in each direction, no safety shoulder, and only an ornamental guardrail to keep drivers’ eyes from straying to the water 135 feet below. Its state is reflected in harrowing accounts from local motorists who have braved the white-knuckle climb to its peak and the equally unnerving descent. In addition, the bridge has a history of deadly vehicle collisions and fires, and a crash rate 66% higher than the state’s.

US Department of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg noted those deficiencies in February remarks at Lake Charles marking a $150 million federal award toward replacing the bridge, through a new grant program funded by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Several past efforts to fix the bridge have fallen short, but earlier this year, Louisiana lawmakers approved a $2.1 billion proposal that would partially be funded by tolls, after a similar plan with higher tolls was rejected in October following pushback from the trucking industry. The state stands to lose federal funding for the project if lawmakers do not finalize a local funding source by this fall.

Four other vulnerable bridges identified by Bloomberg are also in Louisiana — the most in any one state. The list includes the 70th Street Bridge (also known as the Jimmie Davis Bridge), which handles about 25,600 trips daily between Shreveport and Bossier City. The two-lane structure built in 1968 remains open amid ongoing work on a $362 million project to replace it, also funded in part by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law; two other Louisiana spans rated in poor condition have already been closed for replacement since the most recent federal bridge inventory update.

The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development, which owns and maintains the bridge, did not respond to Bloomberg CityLab’s requests for comment, but after the Key Bridge collapse, the agency assured residents that it only keeps bridges open if they are safe for travel.

The other bridges that the Bloomberg analysis singled out present a diverse snapshot of the nation’s inventory of needy infrastructure, from major highway bridges to tiny urban and rural connectors. Three of the spans most in need of repair are in Chicago, a city that must maintain more than 300 bridges and viaducts.

Some structures, like the Locks Plaza bridge in Lockport, New York, are landmarks worthy of historic preservation. Known locally as the “Big Bridge,” it’s a curiously engineered structure that crosses the Erie Canal on a diagonal and was billed as one of the world’s widest when it opened in 1914. Officials say that the bridge is currently undergoing rehabilitation, but remains open to traffic. “If a bridge was deemed unsafe for travel it would be closed,” Glenn Bain, a spokesperson for New York State Department of Transportation, said in a statement.

The oldest bridge among those identified by Bloomberg is the Kernwood Bridge, a swing-span-style drawbridge over the Danvers River between Beverly and Salem, Massachusetts. Built in 1907, its deck and superstructure were deemed poor, and its substructure given a “serious” rating. On average, 4,700 daily trips are made on the bridge, which is slated to be replaced — but the process will likely not begin until at least 2027.

Weighing Priorities

How US bridges get prioritized for repairs or replacement — and access funding to do the work — depends on a complex balance of not just the structure’s age and condition, but also on how heavily they are used, their importance to the broader region, and a mix of local, state and national political considerations and funding sources.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, signed in November 2021, includes $40 billion over five years for bridge repairs and replacement. But overall, the US faces an estimated $125 billion backlog of bridge repair needs, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers, which gave the country’s bridges an overall C rating in its most recent infrastructure report card.

“Events like the Key Bridge’s collapse underscore that not all infrastructure is of equal impact to the country, to states — even to cities,” said Adie Tomer, a senior fellow at Brookings Metro, who focuses on infrastructure policy.

The Port of Baltimore is one of the busiest on the East Coast, and the bridge served as a vital artery for commuters and freight truckers. Its closure, Tomer says, “actually hurts the cardiovascular system of the metropolitan economy.”

Maryland has already received $60 million in federal emergency funds to begin the cleanup process, and President Biden pledged that the federal government will cover the estimated $2 billion price tag to rebuild the bridge as quickly as possible. But within days of the collapse a debate emerged in Congress over the proposal, with some Republican lawmakers insisting that funding should be accompanied by unrelated spending cuts.

Where funding will come from remains unclear, and could have implications for needy bridges elsewhere. It’s possible that Congress creates a new source of funding, which won’t affect any federal maintenance aid sought for other spans nationwide, according to Jeff Davis, senior fellow with the Eno Center for Transportation. That’s what happened in 2007, when lawmakers made a special appropriation of $195 million to replace the felled I-35W Mississippi River Bridge, and in 2005 when Congress appropriated $2.75 billion to the emergency relief fund for expenses related to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Of that, $629 million went toward the reconstruction of the heavily damaged I-10 bridge spanning New Orleans and Slidell, Louisiana.

But lawmakers could also tap dollars in existing programs, including those established in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. “If the Biden administration ends up choosing to use the competitive dollars from programs that the USDOT controls, then yeah, that $2 billion is not going to some other bridge around the country,” said Yonah Freemark at the Urban Institute, which tracks how federal infrastructure investments are distributed. “That’s just the reality.”

Ultimately, insurance payouts could help cover the costs of the project, as US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in March. But the timeline for resolving the multiplicity of claims could, by one estimate, take up to four years, and historically, funds for replacing bridges destroyed in maritime mishaps have come from taxpayers, not insurance payouts.

The Key Bridge’s collapse might have other broad ripple effects on the US bridge network, Tomer says, by drawing awareness to the importance of maintaining infrastructure and encouraging lawmakers to devote more funding to repair work. In 2026, the next Congress is set to rewrite the surface transportation authorization act that governs how more than half of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s $1.2 trillion is spent. “It could create the opportunity for more total funding to flow to bridges that could use the investment,” he said.

Of course, that also rests on the results of November’s presidential election — and whether replacing the Key Bridge can remain a national priority. But as Tomer puts it, “this is where the apolitical nature of infrastructure plays to the country’s benefits. Behind the scenes, there is no member of Congress that doesn’t support investing in safe bridges and interstate commerce.”

--With assistance from Marie Patino.

Most Read from Bloomberg

- Tesla Soars on Tentative China Approval for Driving System

- HSBC CEO Quinn Unexpectedly Steps Down After Almost 5 Years

- Stocks Trade for 390 Minutes a Day. Increasingly, Only 10 Matter

- US Warns ICC Action on Israel Would Hurt Cease-Fire Chances

- Yen Sparks Intervention Suspicion After U-Turn From 1990 Lows

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

2024-04-29T14:40:47Z dg43tfdfdgfd